We are delighted to have the excellent Jo Clubb agree to write a blog for us. Admittedly, this blog is a little more high-brow than our usual ramblings, so thanks to Jo for adding some class to our library. Jo has recently broken into the American sports scene, working as a sports scientist with the Buffalo Sabres NHL, bringing with her expertise from her years in football (..soccer) in the UK (previously with Chelsea & more recently with Brighton & Hove Albion FC). What makes this blog extra special to us is that Jo already has an excellent blog page of her own that is read and commended worldwide (Sports Discovery – here). Jo demonstrates how & why sports science plays a massive part in return from injury in professional sport…

Introduction:

Training Stress Balance and the Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio are real buzz words in Sports Science at the moment. They also have important implications for the Physiotherapy and Conditioning communities in terms of rehabilitation and Return To Play.

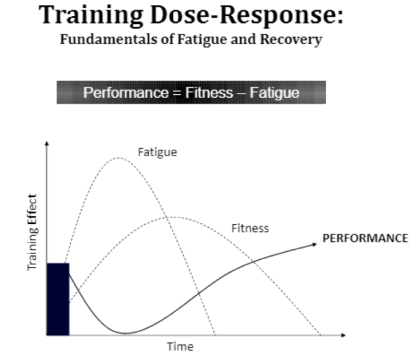

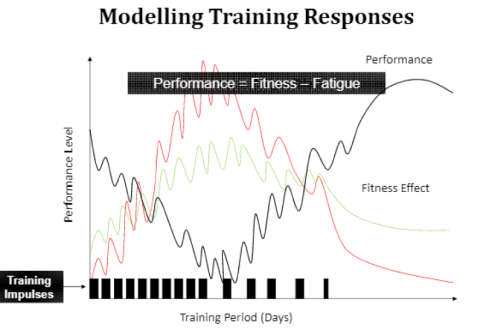

This concept is derived from Banister’s modelling of human performance back in the 1970s (and then later added to by Busso in the 1990s) that put forward an impulse-response model to predict training load induced changes in performance. If we consider a single block of training, this stimulus will have a temporary negative influence represented as ‘fatigue’ but over a longer time frame will have a positive influence, represented as ‘fitness’. Performance will consequently be a product of the Fitness Fatigue relationship (see Figure 1). Within this theoretical model of Training Theory, it is suggested that with regular training stimuli we can manipulate these processes of fitness and fatigue via training load, recovery and overcompensation, to have a positive influence on performance (see Figure 2).

Figure 1: Used with permission from Professor Aaron Coutts

Figure 2: Used with permission from Professor Aaron Coutts

The Acute:Chronic Workload

Whilst this concept of training stress balance has been cited since these early, groundbreaking days, it has recently been developed into the acute:chronic workload ratio by Tim Gabbett and colleagues, which they suggest is the best practice predictor of training-related injuries (Gabbett, 2015).

It has previously been represented as a % for Training Stress Balance, but the focus now seems to be on utilising it in a ratio form, for example:

= Acute workload / Chronic workload

= 3000 (Au) / 4000 (Au) = 0.75

In this example acute workload is represented as the total load over the previous one week and chronic workload is the average weekly load for the previous four weeks, both utilising an arbitary unit (Au) such as session RPE.

So a ratio below 1, as per the above example, suggests the athlete is more likely to be in a state of “freshness”; their load over the past week has been less than their average weekly load over the past four weeks.

On the other hand a ratio above 1 represents that the workload over the past week has been greater than the average weekly load over the past four weeks, so they may be more likely to be in a state of “fatigue” and potentially less prepared for that workload. Recent research has suggested a ratio greater than 1.5 represents a “spike” in workload that is related to a significantly higher risk of injury (Blanch and Gabbett, 2015 here).

Training and Game Loads and Injury Risk

Tim Gabbett and his colleagues have collected consistent data within the training environment, statistically modelled the relationships between workload and injury risk, applied their model to help reduce injury risk in the training environment and published this data – for me this is the gold standard process of Sports Science and a method we should strive to replicate within each of our own environments. The relationship between workloads and injury risk has included just some of the following research:

- Running loads and soft tissue injury in rugby league (Gabbett and Ullah, 2012)

- Training and game loads and injury risk in Australian football (Rogalski et al, 2013; Colby et al, 2014)

- Pitching workloads and injury risk in youth baseball (Fleisig et al, 2011)

- Spikes in acute workload and injury risk in elite cricket fast bowlers (Hulin et al, 2014)

- Acute:chronic workload ratio and injury risk in elite rugby league players (Hulin et al, 2015)

I can talk about this all day (and probably will in a number of other blogs); however the focus of this specific blog is on the application in the rehabilitation environment so I will leave it at that for now. If you do want to read more of this topic, I highly recommend reading the following OPEN ACCESS paper:

Rehabilitation

There is plenty of application to this approach in the training environment however; it is just as important in the rehabilitation setting as highlighted in the following paper:

Has the athlete trained enough to return to play safely? The acute:chronic workload ratio permits clinicians to quantify a player’s risk of subsequent injury (Blanch and Gabbett, 2015).

Rehabilitation is without doubt a very complex continuum in which medical staff assist the athlete through early stage rehabilitation to the multifaceted return to train, play and performance decisions, which I have tried to tackle previously (here) and specifically for hamstring injuries (here). Previous to the paper by Peter Blanch and Tim Gabbett much of the literature on Return to Play failed to acknowledge the consideration of the progression of load in the RTP decision.

Often the evaluation of health status that directly influences the Return To Play decision may incorporate instantaneous physical testing results such as isokinetics or force plate assessment, as well as functional on pitch activity profile targets such as peak speeds, distances, high intensity running and velocity changes. Whilst there is no doubt these have their place, there also needs to be consideration for the loading achieved throughout the rehabilitation continuum in preparation for the acute and chronic loading demands of training and matchplay.

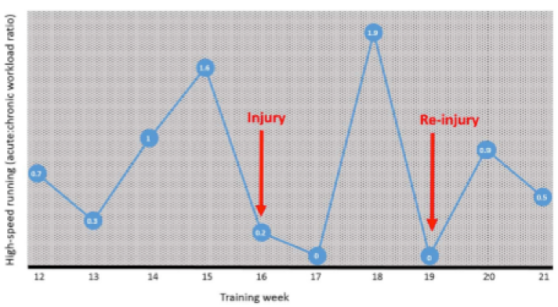

Blanch and Gabbett present a real world example from rugby league (Figure 3) in which a player suffered a hamstring injury after an acute:chronic workload ratio of 1.6 in training week 15. After two low-minimal weeks of high speed running due to the injury, the acute:chronic workload three weeks later spiked to 1.9 (presumably as high speed running was reincorporated into the rehabilitation phase in week 18) and then suffered a reinjury. This example also reminds us to consider which measure(s) of load is most relevant to each sport, injury and individual. High speed running is no doubt important to a hamstring injury but may be of less importance with other sports and injuries. The acute:chronic workload ratio can be applied to any of the variables you collect and may represent a different picture across different metrics.

Figure 3: From Blanch and Gabbett (2015), p2.

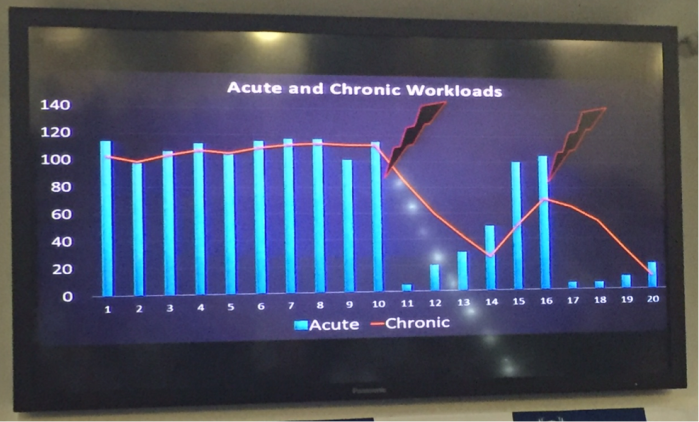

Rod Whiteley recently gave an excellent presentation at the Aspire Monitoring Training Loads conference entitled “The conditioning-medical paradox: should service teams be working together or as enemies on the training load battlefield?” He applied Tim Gabbett’s work to rehabilitation workloads and related it to the “chronic rehabber”; s/he who never gets to build a consistently high base of chronic workload to prepare themselves for returning to the training environment, so suffers a spike in acute:chronic workload and then a reinjury (Figure 4). He called upon us to “fundamentally rethink how we’re reintroducing the athletes” as well as breaking down the traditional silo structure between medical staff and conditioning staff.

Figure 4: Presented by Rod Whiteley, Aspire Monitoring Training Load Conference February 2016

Now we obviously cannot keep athletes away from the training environment forever and nor would we want to. However, it seems avoiding spikes in acute:chronic workloads with returning athletes may help the transition into return to training and competition, and to reduce reinjury risk. This may be achieved via further progressing the load achieved prior to RTP and/or reducing the load from reintegration by using modified training (or a mixture of both). In reality it may not be as simple as that – a major challenge for the Science and Medicine team is to manage expectations of both the athlete and the coaches. I’m sure if the athlete is looking good and undergoing a substantial training load there will be pressure to incorporate them into training.

I believe this paper highlights the need firstly to consider and plan (where possible) the progression of load throughout rehabilitation, end stage and continued into training and games. Whilst the athlete may be physically prepared for the demands of a one off training session, we must also pay attention to the demands in terms of acute and chronic load. It also highlights the need to consider the consequences of each decision relating to loading of the athlete; whether that is the decision to offload the athlete for a day (which may of course be truly necessary based on the clinical presentation) or the decision of how much load to put the athlete through day to day. In another example from the Blanch and Gabbett paper the authors put forward a representation of an injured player’s Return to Play and demonstrate how the variations in load in that week directly influence the likelihood of injury – i.e. 90% acute load would return an 11% likelihood of injury, compared to 120% which would be related to 15% risk.

Whilst injuries are undoubtedly complex, multifaceted and influenced by many factors, and statistical modelling of the risk has its own limitations, it seems the evidence is strong enough to suggest that the interaction of acute and chronic load through rehabilitation and RTP is another piece of the puzzle that is worthwhile considering.

Jo Clubb (@JoClubbSportSci)

References

Banister EW & Calvert TW. (1975) A systems model of training for athletic performance. Aust J Sports Med; 7: 57-61.

Blanch P & Gabbett TJ. (2015) Has the athlete trained enough to return to play safely? The acute:chronic workload ratio permits clinicians to quantify a player’s risk of subsequent injury. Br J Sports Med;0:1–5. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095445

Busso T, Hakkinen K, Pakarinen A, et al. (1990) A systems model of training responses and its relationship to hormonal responses in elite weight-lifters. Eur J Appl Physiol; 61: 48-54.

Colby MJ, Dawson B, Heasman J, et al. (2014) Accelerometer and GPS-dervied running loads and injury risk in elite Australian footballers. J Strength Cond Res; 28: 2244-52.

Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Cutter GR, et al. (2011) Risk of serious injury for young baseball pitchers: a 10-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med; 39: 253-7.

Gabbett, TJ. (2016) The training-injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder? Br J Sports Med doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095788

Gabbett TJ & Ullah S. (2012) Relationship between running loads and soft-tissue injury in elite team sport athletes. J Strength Cond Res; 26:953-60.

Hulin BT, Gabbett TJ, Blanch P, et al. (2014) Spikes in acute workload are associated with increased injury risk in elite cricket fast bowlers. Br J Sports Med; 48: 708-12.

Hulin BT, Gabbett TJ, Lawson DW, et al. (2015) The acute:chronic workload ratio predicts injury: high chronic workload may decrease injury risk in elite rugby league players. Br J Sports Med; Published Online First: 28 Oct 2015. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094817doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094817

Rogalski B, Dawson B, Heasman J, et al. (2013) Training and game loads and injury risk in elite Australian footballers. J Sci Med Sport; 16: 499-503.

[…] https://plinthsandplatforms.wordpress.com/2016/03/11/has-the-athlete-trained-enough-to-return-to-pla… […]

LikeLike

Another reference for anyone interested in this topic, especially in terms of Training Stress Balance, is this exceptional article by Dr Andy Coggan from 2008 on the Training Peaks website:

http://home.trainingpeaks.com/blog/article/the-science-of-the-performance-manager

LikeLike

thanks for sharing this information. I believe there is a lot that goes into re injury and this is one part of it for sure. when I see a re injury I often think that the original cause was not corrected.

LikeLike

[…] and how it can be incorporated into the Return to Play (RTP) decision. You can find that post HERE but much more importantly I would recommend reading the following two BJSM articles if you have […]

LikeLike

[…] the ACWR is also relevant in rehabilitation as we have discussed here: https://plinthsandplatforms.wordpress.com/2016/03/11/has-the-athlete-trained-enough-to-return-to-pla…. This may be another environment where we regularly observe ACWR in excess of 1.5. For example, […]

LikeLike